If you enjoy this story, please take a moment to click the blue “SUPPORT” button on this page.

Lewa’s canister had brought her to a strip of marshland, which she had very quickly decided was not to her tastes. In fact, she had resolved to get as far away from it as possible, by first, identifying, and second, climbing, the tallest tree in the jungle.

To her surprise, it had transpired that she was not the first to have such an idea: a tribe of halflings had already turned that region of the canopy into an extensive network of treehouses, connected by treacherous bridges and vine swings. Not only did they recognise Lewa on sight, but they apparently worshipped her, in honour of the great feats she had performed, or perhaps would perform—their excitable anecdotes were entertaining, but often mutually irreconcilable.

Principally, there was the matter of her elemental power: she was variably described as the spirit of air, a sky-spirit, a nature-spirit, the spirit of the jungle, a levitation-spirit, a spirit of good fortune. In fact, they had argued on this matter right before her eyes—and demonstrations of her supernatural abilities had served not to settle the matter, but to kick up a storm of rebuttals and rationalisations from her devotees.

They did not agree whether she should be a Matoran, or a Rahi (she was a Toa, but they argued that a Matoran could be a Toa too). They did not agree whether she should carry an ax, or a sword (she carried an ax, but one enterprising Matoran had turned it upside-down in her hand and declared it a sword). They did not agree on how she should speak (like a playful breeze, or a thunderous whirlwind), nor whether the focus of her power should be her tool, or her mask (it was neither), nor whether her mask should be coloured green, silver, or gold (and to prove the point, some of them brought out masks fashioned from bark or leaves, daubed in colourful hues, which they wore over their own masks, an act which Lewa found rather perplexing).

The eldest of the group, the one they called Turaga Matau, with whom they had conferred at length in the course of their quarrel, was comparatively taciturn. He had spoken only when spoken to, otherwise watching placidly—but after seeing him deliberately contradict himself for the fifth time, Lewa had realised that he was perhaps the most mirthful of them all.

The only things the Matoran did agree on was that she was green, and that she was great. On both these counts, Lewa was forced to admit that they were correct.

Nonetheless, they had made her prove herself to their satisfaction. She had trounced them in every race through the treetops, swinging faster than their fastest vine-swingers and flying swifter than their swiftest bird-fliers. She had bested them all in a dance-battle. And although her flute-playing was not quite as proficient as the most proficient of the Matoran, she had been the only one to play the flute without touching it.

All in all, her time at Le-Koro had been quite the edifying experience, and she could have stayed far longer—but after Matau had shown her their maskless, she had been gripped by the need to do something about it, something worthy of their stories. So it was that she glided between the trees; the witching hour’s wind. The night-time was not the best occasion for mask-hunting, but she was in her element, her keen eyesight having already adjusted to the near-darkness. The high-flying hero knew that her luck would win out eventually.

And there it was at last: reflecting the light of the moons, suspended between the branches, a lost mask, a lost friend. With a howl of delight, she swooped, reaching out to take it into her hand…

…And suddenly she was stuck, buffeted back-and-forth in midair. Her fingers clung to the mask, but something was clinging to the rest of her, something flashing silver as it shook. A membrane, woven… She realised what it was, and even as she cursed herself for not listening more closely to the Matoran’s stories, a chill passed through her. There were red lights descending from above—had they always been there?

She gathered her power, and sent it thundering at the creature. The gale snapped branches and tore the leaves from the canopy, but the creature’s spindly limbs clutched stubbornly at the threads. When she was done, it resumed its descent, eyes burning. Behind, on the creature’s back, Lewa saw another mask, with empty eyeholes like pits. It planted a leg on her shoulder, and she punched it using her free arm. For the first time, it made a noise—a horrifying hiss—but it was otherwise unperturbed. Another two of its legs seized her arm below the shoulder, and with practised precision, it began to pull.

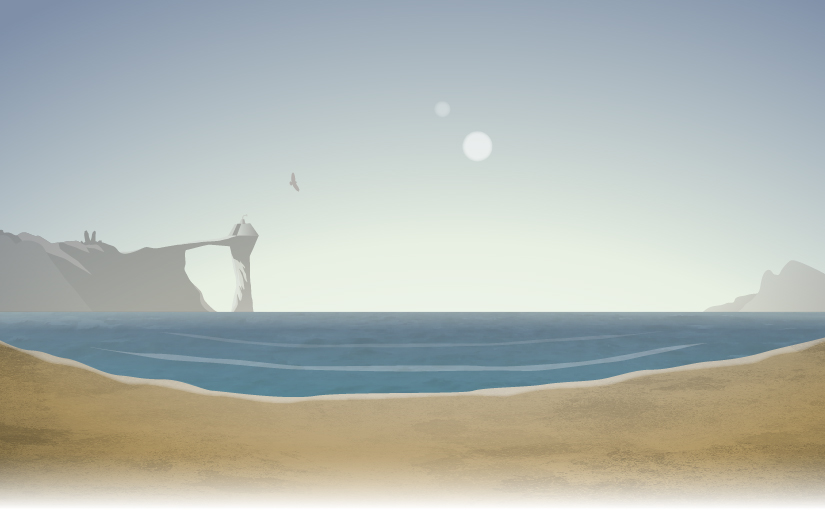

Gali pulled herself through the shallows with her fishhooks, the sun’s heat at her back, the undulations of the seabed before her, and decided that this was where she belonged. She had been born on the wrong side of the shore.

For a time, she swam parallel to the lines in the sand, following them for miles along the coast. And for a time, she was content to let the new sensations wash over her, to feel the way her world responded to her—she and the tide moved as one, went with the flow.

She could have stayed like that forever, but she grew curious, and so with a kick she moved from her course. Antiparallel, she swam, into the ocean that called to her with its immensity.

The seabed fell away, a sharp decline into nothing, and Gali’s heart dropped too: suddenly, there was nothing beneath her, nothing to hold her up. Had she realised sooner, she might have stayed with the sand—but she was already over the precipice. So with nothing to hold her in place, she dove, and found the world. A landscape of coral in more colours than Gali could possibly imagine, teeming with schools of fish. Gone was the tranquility of the shallows: in the expanse, the currents dragged her in every direction. She fought them at first, pushing and pulling at the medium, but she had no destination in mind, and it wasn’t long before she decided to follow the undertow. It was what the rest did, after all.

She shadowed a shark, tailing it at a distance as it chased a shoal. A clawed creature swooped in on winglike fins; as the shark darted away, Gali wondered whether the larger creature held any regard for the fish. Two crabs wrestled, their claws interlocked in determined equilibrium—until the intrusion of a many-headed serpent saw them disengage to fend it off side-by-side. Something blocked out the sun above, and Gali turned onto her back, to see a pod of whales with razor-sharp spines breaching the surface.

There was conflict here, beneath the waves, but also harmony. Everything belonged. Everything but her, she realised. Could they sense the world, as she did? She didn’t just move the water, she felt it, a constant presence enveloping her. Of the other creatures, she felt only their absence in her awareness.

She curled herself up, the world reinorienting around her until the sun hung beneath and the coral above, then kicked off. The pressure buoyed her forward. A flash caught her gaze, and she angled herself towards it. There, on the seabed, was something else which didn’t belong.

It was a mask, like hers.

She reached out with a hook…

…And stopped. Next to the mask, blocked by a formation of pointed stalagmites and stalactites, lay the entrance to a cave. She wondered whether the mask had belonged to somebody—somebody like her—and whether they’d gone into the cave. Why would somebody abandon their mask?

This time, as she pushed her awareness outwards, she did so with intent, searching for a silhouette like her own. It was then that she understood what the cave was. She held out a hook, and used the water to pull the mask to it, before twisting away—and behind her, the cave stood up.

It was faster than she’d expected—its teeth snapped shut right beneath her foot. Its powerful hindlegs propelled it after her, moving a terrifying distance with each stroke. She tried to swim to the surface, hoping that a creature of its size wouldn’t be able to follow—but even with the power of the water behind her, she was tiring fast. Changing tactics, she arced back down towards the seabed; she could still use its size against it, if only she could hide amongst the coral. She swam under an arched formation, and the monster fell behind a little in the course of battering its way through the obstacle. She heard its roar, distorted by the medium it travelled through, and couldn’t help but glance back. Looking at the cloud of destroyed coral, she felt a pang of guilt.

The sight gave her an idea, however. Splitting her attention, she began to manipulate the water above the seabed, stirring up the sand until she was swimming through an opaque soup. Then, she angled herself off to the side, splitting the current of her own creation in two. The next roar from behind seemed no quieter, but neither was it louder, so she repeated the process several more times, veering back and forth across the seafloor. She heard the creature roar again—this time, it wasn’t directly behind her. She’d shaken it off. She looked down at the mask in her hook, and saw her own reflected in it.

When she surfaced, to reorient herself, she saw a strip of green on the horizon. Further than she’d anticipated. She dove again, and let the currents take her back.

As she returned to the shelf, she turned the mask over, and looked through its eyeholes. She remembered what it had felt like, before she’d put on her mask. It hadn’t been her.

What would it mean, to wear another’s mask?

So lost in thought was she, that she almost missed the net drifting towards her. The moment she noticed it, she twisted up out of the way, pushing the woven vines down under her legs using the current. She breached the surface just in time to see a boat capsizing.

“Oh, Mata Nui!” cried a voice from the other side of the boat. “Oh, Gali save me!”

“Okay! One moment!” Gali shouted back.

“What?!”

Gali dove under the boat, and saw kicking feet struggling to find purchase on the side of the capsized boat. She swam across, hooking the sailor around the waist and boosting them up onto the hull. The sailor screamed. Using the water to buoy herself, Gali leaped out of the sea, landing on the boat. The sailor screamed again. “It’s okay,” tried Gali, and the sailor calmed down a little.

“It’s really you,” said the sailor. “You’re really here.” She wasn’t looking at Gali, but at the mask.

“Is this yours?” asked Gali, holding it out.

“No. It- it belonged to Hahli. A friend of mine.” The sailor took it, clutching it close to her chest, and was quiet for a moment. “I’m Macku,” she finally added.

“I’m sorry about your boat, Macku,” said Gali.

“It’s fine, probably,” said Macku, looking down at the water. “It’s the fish I’m worried about.”

“Fish?” echoed Gali. “All the dangerous ones are far from here.”

Macku shook her head. “The ones I caught. They were in the boat, and now they’re all gone.”

Gali was puzzled by this. “What do you need fish for?”

“We don’t need them for anything—but the others, the dangerous Rahi, they get drawn into the bay if we don’t keep it clear of the smaller ones. It’s the only way to keep Ga-Koro safe.” At that, she gave Gali a long look.

“Ga-Koro?” prompted Gali.

“My village. I can show you the way.”

Gali nodded, then hesitated. “What about the fish?”

“I’m thinking maybe we don’t need to worry any more,” said Macku. “Now that you’re here, I mean. You can protect us from the monsters.”

Gali thought of the thing that had chased her, and said, “I can protect you by turning this boat back over and helping you round up the fish again. Then you can show me Ga-Koro.”

Macku agreed, and slid gracefully off the hull. Gali saw that she was a strong swimmer—and in that sense the two of them were alike—but also saw that she was small and fragile, and remembered how frightened she’d been before. Gali stood on the boat, and curled her hooked arms, and drew up a great wave. As the boat rode up, Gali dove off it, shaping the wave behind her to flip the vessel over and guide it back down.

The ocean settled, Macku resurfacing. “I thought you were just going to help push,” she said.

In the end, Gali caught the fish more-or-less by herself; the boat outpaced her, but Macku had no way of seeing below the surface. It turned out that the usual method of fishing was simply to trawl the area repeatedly, relying on lightstones lashed to the boat’s hull to attract the fish. Gali, meanwhile, could detect the fish at a distance and pull them in using currents.

“Last one,” said Gali, using a stream of water to deposit the flopping thing on the deck.

“This is amazing,” said Macku. “This is more than I caught in the first place. You’re going to make everything so much easier for us. I can’t wait to show you the village.”

“Then let’s set a course,” replied Gali. Macku switched the engines on and turned the rudder, and Gali created a swell to push them towards the shoreline.

Ga-Koro was made of lilypads, and its location was marked by a cliffside carved into the shape of Gali’s face. “We used to have close ties to Po-Koro,” enthused Macku. “They carved it for us, isn’t it wonderful? We worked together to redirect the waterfall.” The massive mask was spewing water. Gali wasn’t sure how she felt about that. Macku continued, “That was before… Now, the Rahi make it too dangerous to travel there. But with you here…”

She steered the boat into dock (a lilypad with a hole cut out of it), immediately hopping out and tying it to a post. Gali stepped out too, a little more trepidatiously, concerned that her weight would just cause the plant to sink. It sagged a little, but was surprisingly firm.

“Hey, Orde!” Macku hollered at the nearest hut—constructed from strips of seaweed, folded together and sealed somehow. “I’m back, and I brought Toa Gali with me!”

“Wow, Macku. Next time, you should try and catch the Great Spirit!” came the reply. Someone emerged from the hut—someone Macku’s height—only to immediately stop in his tracks. “I- I-”

Gali waved a fishhook.

Orde ran away.

“I think I scared him off,” said Gali, as Macku laughed.

He returned in seemingly no time at all with an entire crowd. They swarmed around her, before parting to allow someone through.

“Toa Gali, we are honoured to finally meet you. I am Nokama, Turaga of Ga-Koro,” she said. She was ganglier than the others, and she leaned on a trident for support. “We Matoran have awaited the arrival of you and your siblings for many years.” Looking over at Macku, she said, “That mask… it seems today we greet friends old and new. Let us waste no time.”

Nokama led a procession across the walkways between the lilypads, to a large hut in the centre of the village. Inside, more Matoran were laid out on beds of reeds. “What happened to them?” asked Gali.

The Turaga didn’t answer, instead walking to the very back of the hut, beckoning Macku to follow. “Would you do the honours?” she said to the Matoran.

Macku kneeled down next to one of the Matoran. Barefaced, the Matoran looked back up at her. She held out the mask, putting it on the Matoran—who immediately sat up, and said, “How long was I lying here?”

“Hahli!” Macku cried, pulling her into a hug.

Turning back to Gali, Nokama explained, “Hahli was the first of us to lose her Kanohi to the Rahi. Sadly, she has not been the last—but she is the first to return to us. You have brought us hope for the rest. Thank you.”

“Is this my purpose?” asked Gali. “To find these… Kanohi?”

“After a fashion. Will you walk with me?” Seeing Gali’s nod of response, Nokama raised her voice to address the assembled Matoran. “Toa Gali and I have much to discuss. We are not to be disturbed. See that the supplies are cleared from Hahli’s home.”

The Matoran began to disperse in groups. Nokama led Gali to one of the nearby huts, and moved a screen over the doorway behind them. The hut was homely, lit not by lightstones, but by a jellyfish swimming around in a glass bottle hanging from the roof. There was a sizeable hole cut in the lilypad in the centre of the hut, and the blue glow reflected from the water beneath. Nokama sat down, letting her legs dangle into the water, then looked back up at Gali.

“You cannot stay here,” said the Turaga.

Gali glanced over at the screen. “Did I do something wrong?” she asked.

“No—but with time, you might. If I could have my way, you would never leave Ga-Wahi, fighting on our behalf, recovering our fallen friends. The ocean of this world is beautiful, and we have feared it for altogether too long. Our very way of life has become defined by fear. Makuta’s twilight draws in ever-closer, all around us—but that is not merely Ga-Koro’s problem. That is Mata Nui’s problem.” She kicked her legs, agitating the water. “My brothers and sisters have quarrelled, in the past. On this very matter, in fact: the matter of what the Toa are to do.”

“So there are others like me,” murmured Gali, looking down at her hooks.

“Yes; six of you, though you all have your differences. The same is true of the Turaga—we have allowed those differences to divide us. You must not make the same mistake. You must find them, Gali, and ensure that they remain united.”

“How will I know where to look?” Gali asked.

“They will have found their way to their respective villages, much like yourself. Po-Koro and Ta-Koro are closest, but Ta-Koro is far inland, and the way to Po-Koro is infested with Rahi. You should follow the coastline south, instead. Beyond the southern tip of the island, you will come across an estuary, which will lead you into the jungle. The tallest tree in that jungle marks the centre of Le-Koro—though Turaga Matau and I have had our disagreements, he will help you. If you hurry, it should be possible for you to make it there by nightfall.” Using the trident for support, Nokama rose. Once she was back on her feet, she pointed the trident at the pool. “It is best if you are not seen leaving, lest the more foolhardy amongst my people decide to follow you.”

“What will you tell them?” asked Gali.

“I will tell them the truth: that you are working to save our friends. The masks are a distraction, Gali—Makuta lies below. Once he is defeated, we will have all the time in the world to bring them back.”

Gali inclined her head. “I won’t let you down, Turaga Nokama,” she said, stepping towards the hole in the floor. Nokama bowed in return, and with that, Gali slipped down into the water.

Down in the lowest section of the Great Mine, Toa Onua listened patiently as the Matoran explained his plan to solve an unsolvable problem.

“-But this layer of protodermis is totally impenetrable,” said Nuparu. “You can hit it as hard as anything, but your tools will just bounce straight off it—or, if you’re an insane monster freak called Taipu, they snap right in half. Unstoppable force, meets immovable object, meets fragile pickaxe.” He gave the Turaga walking alongside them a meaningful look. “Seriously, Whenua, when will you get off my case and start focusing on the real drain on our resources? That guy singlehandedly accounts for two-thirds of our equipment budget, and I’m not even exaggerating there, okay, I am exaggerating, but it’s a nontrivial amount of broken picks. They’re like twigs in his big stupid hands. I’m not joking, I saw him snap one in half using just his fingers. Just to see if he could!”

“That sounds like the kind of experiment you would be interested in, Nuparu,” said Whenua mildly.

“Well yes, I was the one who asked him to try it, but that’s besides the point—if a Ko-Matoran told you to roll down Mount Ihu, would you do it? Of course not! But that’s just the kind of guy Taipu-”

“Toa Onua will have plenty of time to meet Taipu later,” said Whenua, cutting him off at last. She pointed at the centre of the cavern using the drill she carried. “Why don’t you tell us what these machines of yours do?”

“Right! Onua, did Turaga Whenua tell you that I’m responsible for the designs of all our mining equipment?”

“No,” rumbled Onua. “You did.”

“Oh dear. I hate repeating myself. Well, regardless, I am responsible for the designs of all our mining equipment, and after this discovery finally gave Whenua just cause to let me back at the stockpiles, I’ve come up with some truly remarkable results. Astonished myself, even,”

“To clarify, Toa Onua,” interrupted Whenua. “Nuparu here has yet to break through this layer of rock.”

“Well, I suppose that was what was so astonishing, I really thought I’d get it first try,” said Nuparu, gesturing at the nearest machine. “Attempt number one: the Granite Grinder. One of my finest creations, really: quadrupedal base for mobility and stability, in-built debris crane, fully-autonomous operation, dual-axe action. A marvellous piece of engineering—but, dare I say it, too marvellous. It was just trying to do too much. In fact, I’ll admit it, I lost focus a little. It works just great on granite, but this particular problem was really a matter of brute strength, and I lost sight of that.”

“So for your second attempt, you made a motorcycle,” Whenua said flatly.

“So I made a motorcycle! Yes, I was speaking with hindsight there. It took until after the second attempt to see what was really wrong with the first attempt—but I did make a very fine motorcycle. One of my finest creations, even. Ingenious method of getting the chisels up to speed, starting with horizontal velocity before converting it to vertical force. It’s really informed my latest attempt.” In the middle of the flat area of rock cleared from the cavern floor, a great scaffold of wood had been constructed, supporting large boulders tied to pulleys. Suspended at the centre of it was a gleaming drill. “This time, I’m still letting gravity do a lot of the work, but at a much greater scale, introducing a rotational component to the point of contact. It’ll shock the protodermis and scrape away a layer of material—or at least, it will in theory. We were about to test it when the news broke of Toa Onua’s arrival.”

“There was no need to wait on my count,” said Onua, waving a claw.

“Are you kidding, Onua?” Nuparu said. Whenua glared at the Matoran. “I was trying to avoid a very specific circumstance—see, although I am sincerely confident in this design, there’s no getting around the fact that neither of my previous attempts were successful, so in the unlikely event that the same proves true of this one, I didn’t want you coming down here and showing me up. Which is why you’re going to try first.”

“Me?” asked Onua.

“You are the strongest of the Toa,” elaborated Whenua. “If anyone is capable of breaking through on strength alone, you must be able to.” She smiled. “What, you think I brought you down here just to listen to Nuparu?”

“Okay,” said Onua. “Where would you like me to try?”

“Here will do.” She tapped the floor with her drill.

Rubbing his hands together, Nuparu said, “I don’t know what I’m going to do if you pull this off. Maybe I should just dismantle it! It’ll be obsolete technology.”

Onua squared himself in place, at a distance from the others, and raised a claw in the air. He felt the earth all around them, tightly packed—but below, there was only an absence.

Tensing his entire body, he brought the claw smashing down onto the surface.

He stood motionless for a moment, before stepping back.

“Well, what do you know,” said Nuparu. There wasn’t a mark to be seen. The Matoran turned away, and began beckoning to the others gathered around his invention.

Whenua murmured to Onua, “I really thought that would work.”

“Perhaps Nuparu can do it,” replied Onua.

“If he does, I don’t know that I shall be able to talk to him afterwards,” Whenua remarked.

The Matoran were ready. Nuparu raised a hand in the air. “Mata Nui, give me the strength of a thousand Onuas!” he shouted. He brought his hand down. The boulders were released, and immediately the drill became a shining blur. It plummeted to the surface, colliding with a screech of sparks. After a few cacophonous seconds, a team of Matoran hauled another pulley and the drill was retracted.

When it was safe to approach, they gathered at the base of the construct. Nuparu crouched down to examine the blackened surface. He poked it with a finger. A miniscule chip of protodermis shifted to one side.

“While this is excellent work, Nuparu,” began Whenua, “we have no way of knowing how thick this layer-”

The Matoran punched a fist in the air. “-Move over, Toa Onua, and arise, Toa Nuparu!”

A torrent of water blasted the spider, tearing through its web. Lewa started to fall, so she called the air to her, landing softly on her feet. A moment later, with an almighty crash, the spider fell too.

Lewa looked around, and saw a tall blue figure pointing a pair of hooks at the spider. In the air before the stranger, droplets of moisture were streaming together to form a shimmering orb.

The spider was charging at the stranger. Gone was its methodical deliberation—now it moved with unchecked aggression, far faster than seemed possible for something of its size. “Look out!” Lewa shouted. Realising the danger, the newcomer scattered the orb and leaped upwards, hooking a branch above and using the purchase to pull the rest of her body out of the way—but the spider immediately began climbing the tree. Moving fast, Lewa ran towards it and jumped, flying feet-first into its abdomen and knocking it from the trunk. She hit the ground and rolled as the spider tried to right itself.

“You have its mask!” shouted the stranger from the branch. “We should flee!”

“No—I have the Matoran-mask it was guarding,” Lewa replied. She circled around the spider, but its flailing limbs made it impossible to get close. “It still wears the Makuta-mask on its back. It’s too dangerous to leave here.”

“What do you suggest?”

“I can trap it, if you can distract it, keep it in one place.” Lewa ran to a nearby tree, and took a swing at it with her ax. The spider had successfully turned itself back over, but the stranger—the spirit of water whose name escaped Lewa—was gathering another orb, not of water, but of mud. Lewa swung at the trunk again, and it creaked. Above, birds rose from its branches, and Lewa realised too late she was about to destroy their home.

The Toa of Water jumped down from her branch and sent the ball of mud flying at the spider, hitting it directly in the eyes. Seeing an opportunity, Lewa lined herself up and kicked the tree. It snapped and toppled, smashing branches as it fell, directly onto the spider. The monster roared, but its legs were pinned. Lewa swept in, landing gracefully on its back, and plucked the other mask away. Immediately, it ceased thrashing.

Lewa hopped down to the ground. “Hold these for a moment,” she said, passing the masks to the other Toa. Holding her ax with both hands, she chopped through the trunk next to the spider, allowing the two pieces to roll aside. The spider rose, and looked at the Toa passively, before wandering away.

“You fought well, sister,” said the other Toa.

“Call me Lewa. And likewise to you…”

“Gali,” she finished. “Toa of Water.”

“Toa Gali,” Lewa nodded. “You’re a long way from your domain. How did you find me?”

“Turaga Matau told me which way you’d gone… and from there, I simply had to follow the wind,” Gali replied. “What was that thing?”

“I believe the Matoran called it a Fikou-Nui,” said Lewa. “They make webs to catch birds and Matoran.”

“And Toa,” laughed Gali.

“It’s dark, I couldn’t see,” said Lewa. “But yes, thank you for your help. I’ll get these masks back to Le-Koro, and let you be on your way.”

Gali passed the masks back, but said, “Actually, perhaps I can accompany you back. We need to talk about our fellow Toa.”

“Hmm,” replied Lewa. “Okay. But only because you caught up to me before. I’ll race you.” With that, Lewa summoned a great gust of wind and flew up to the canopy.

She heard Gali shout from down below, “I said we needed to talk!”